|

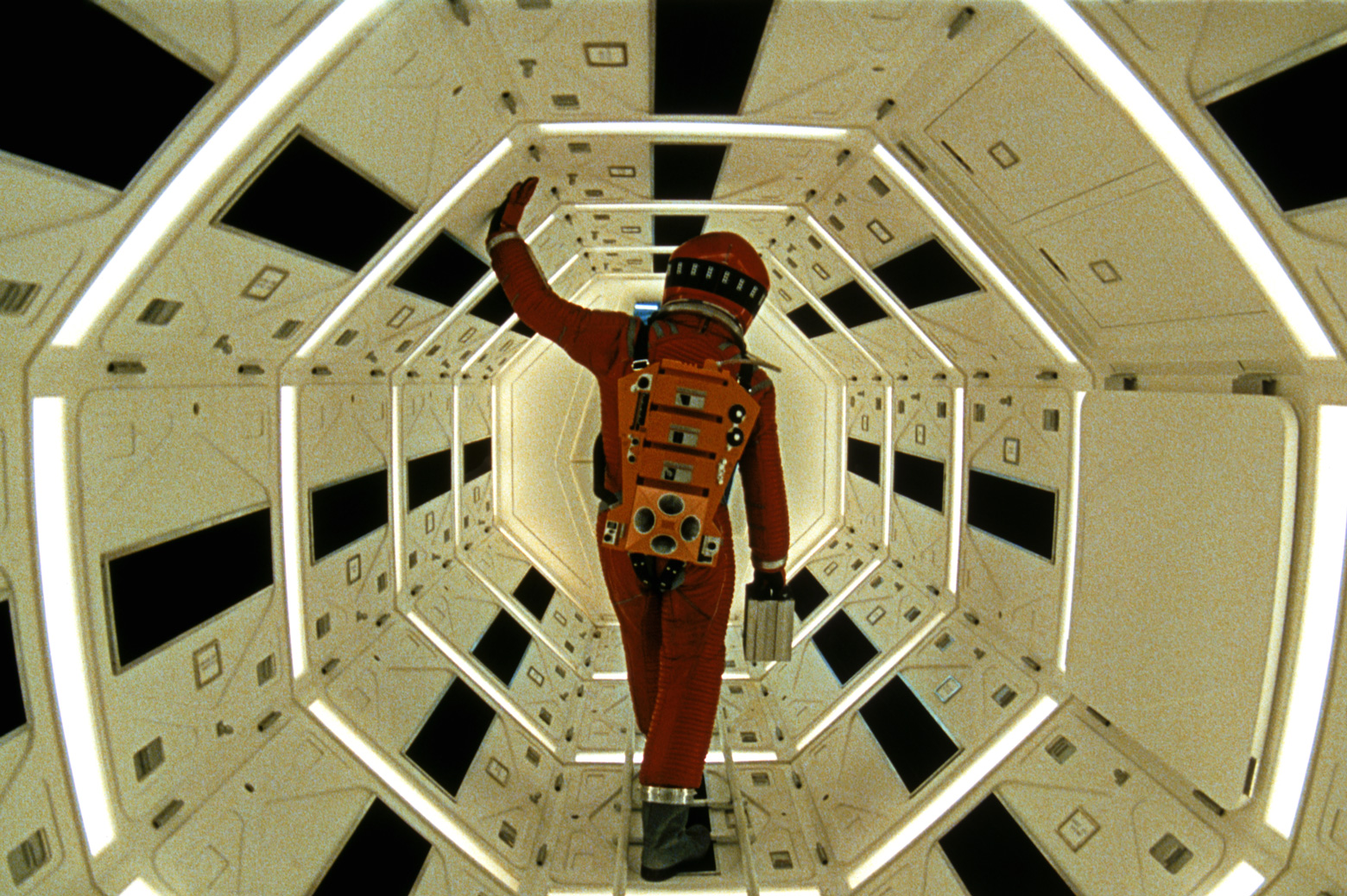

| This is from 1968? And I'm expected to believe that? |

July 20th, 1969. A truly astronomical feat of humankind. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people on the moon, as millions of folks watched, absolutely enraptured, from their TVs sets here on good ol' Earth.

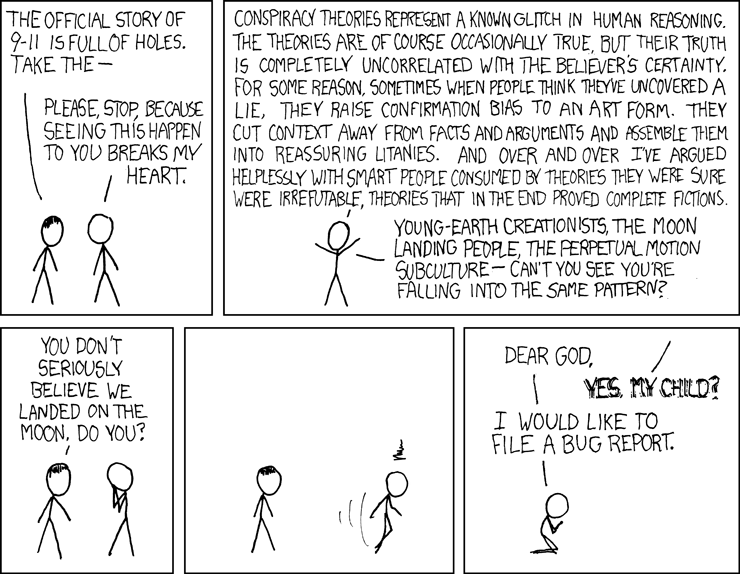

And, like most historic monuments in our scattered timeline of existence, popped up the omnipresent scatterbrains - the conspiracy theorists. Because, well, why shouldn't they?

|

| There's always an xkcd for that |

There was one singular name on the entire blasted index box.

The name was Stanley Kubrick.

It was fuzzily familiar, and a few quick clicks revealed why. The poor fellow had had the misfortune of directing a "cinematic masterpiece", a true trailblazer who walked so every other space movie could run - Stanley Kubrick was the director of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/stanley-kubrick-b225179ffbd04cb48376f3920c15ace4.jpg) |

| What have you done, Mr Kubrick? |

Why was this movie so relevant, and what made people think that this man - this one, right here - was responsible for the world's greatest hoax?

The best way to get to the bottom of this was to watch the movie.

| Arthur C. Clarke, one of the "big three" of 20th Century science fiction, alongside Issac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein. |

The pyramid was buried billions of years ago, and has a force field around it. The field is breached twenty years in the future with advancements in atomic energy, destroying the pyramid in the process.

The pieces are found to be far more advanced than human technology, suggesting that it was placed by aliens. The narrator hypothesizes that now that humans have reached sufficient advancement to break the pyramid, it had alerted the aliens of our present state (i.e., the Sentinel), and they shall now "turn their gaze upon us", whatever that ominous sentiment means.

|

| Cover of "The Sentinel" anthology of Clarke's short stories |

Clarke absolutely despised the idea that 2001 was "adapted" from this story, and compared it to saying an oak was "adapted" from an acorn. 2001 just has tons more to unpack. Let's begin.

You know a movie is ambitious when it chooses to begin from the Dawn of Humanity. It opens on the South African landscape, as a tribe of hominins are driven away by another tribe. Overnight, a large black precisely cut slab of...something appears in their midst. This is the famous "black monolith", arguably one of the most iconic features of science fiction. We don't really learn much about it - except that it is of extraterrestrial origin, and is usually at the sight of some massive change in human history. In this case, it is the hominins learning to use tools.

|

| Well played, Greta Gerwig |

The Barbie Movie, 2023, paid tribute to this opening sequence recently. It involved little girls smashing up a doll, with the monolith being replaced by a giant Barbie. Radical.

Fast forward a few million years, because yes, it's ambitious, we've talked about this, we meet a certain Dr. Floyd. His trip from the earth to a moon base is shown in a few clips (a quick shot of him sleeping was enough to lure my classmates into half-amused curiosity: "Is he dead?" "I don't know, bit early for that, isn't it?").

He exchanges bleak, superficial pleasantries with Russian scientists, who are concerned that Clavius, a lunar outpost, does not have a functioning communication system, amid rumours of an "epidemic" (cue uncomfortable, strained smiles from across the classroom). Dr. Floyd refuses to open up, calling the information highly confidential.

He proceeds to wish his daughter a happy birthday through - can you believe it? - video call! ("I bet they added this scene just to flex the video call", declared my fellow audience). Finally, he heads to his actual mission - an artefact which was buried under the lunar surface for billions of years. Also, it's a black monolith.

Dun-dun-DUUUUUN

Dr Floyd and his team examine the object, when it starts emitting high-powered frequencies.

We cut to eighteen months later.

An American spacecraft in en route to Jupiter (the past had high hopes for the people of 2001). On board, we meet Frank and Dave and three other scientists who are inside a sort of "hibernation pod". Most of the spacecraft's operations are controlled by an artificial intelligence called HAL. HAL reports a failure of an antenna, Dave sets out to find the error using the EVA pod. However, despite many tries, no problems are found.

|

| Meet HAL |

Dave and Frank are concerned about HAL's behaviour, so they enter an EVA pod, where HAL cannot hear them, and agree to disconnect HAL if it is found to be wrong. Unbeknownst to the astronauts, HAL has been following this conversation by lip reading.

|

| You're never really safe, are you? |

When Frank is outside the ship to replace the antenna pod as discussed, HAL suddenly takes control and sends him adrift. Dave tries to rescue Frank, and while he is outside, the other scientists in hibernation pods are killed by HAL by switching off their life functions. Dave retrieves Frank's corpse, but HAL refuses his re-entry into the ship, saying their plan to disconnect it will destroy the purpose of the mission to begin with.

Dave is forced to let Frank go.

Using some rather questionable applications of vacuum and matter, Dave opens up one of the ship's airlocks and enters anyway. He rushes into HAL's processor and begin disconnecting HAL's circuitry before it can continue this murderous rampage. This part of the film is arguably the most terrifying, with HAL's monotonous pleas for help ringing in the background combined with Dave's determined heavy breathing.

|

| Boy was this terrifying |

Whence he is done, a recording by Dr Floyd plays conspicuously, wherein he reveals that the mission's real objective is to investigate a radio signal sent by the monolith on the moon to Jupiter.

As The Blue Danube plays grandiosely in the background, Dave reaches Jupiter to find a third, much larger monolith in orbit around the planet.

From here on, the film ceases to make any immediate sense.

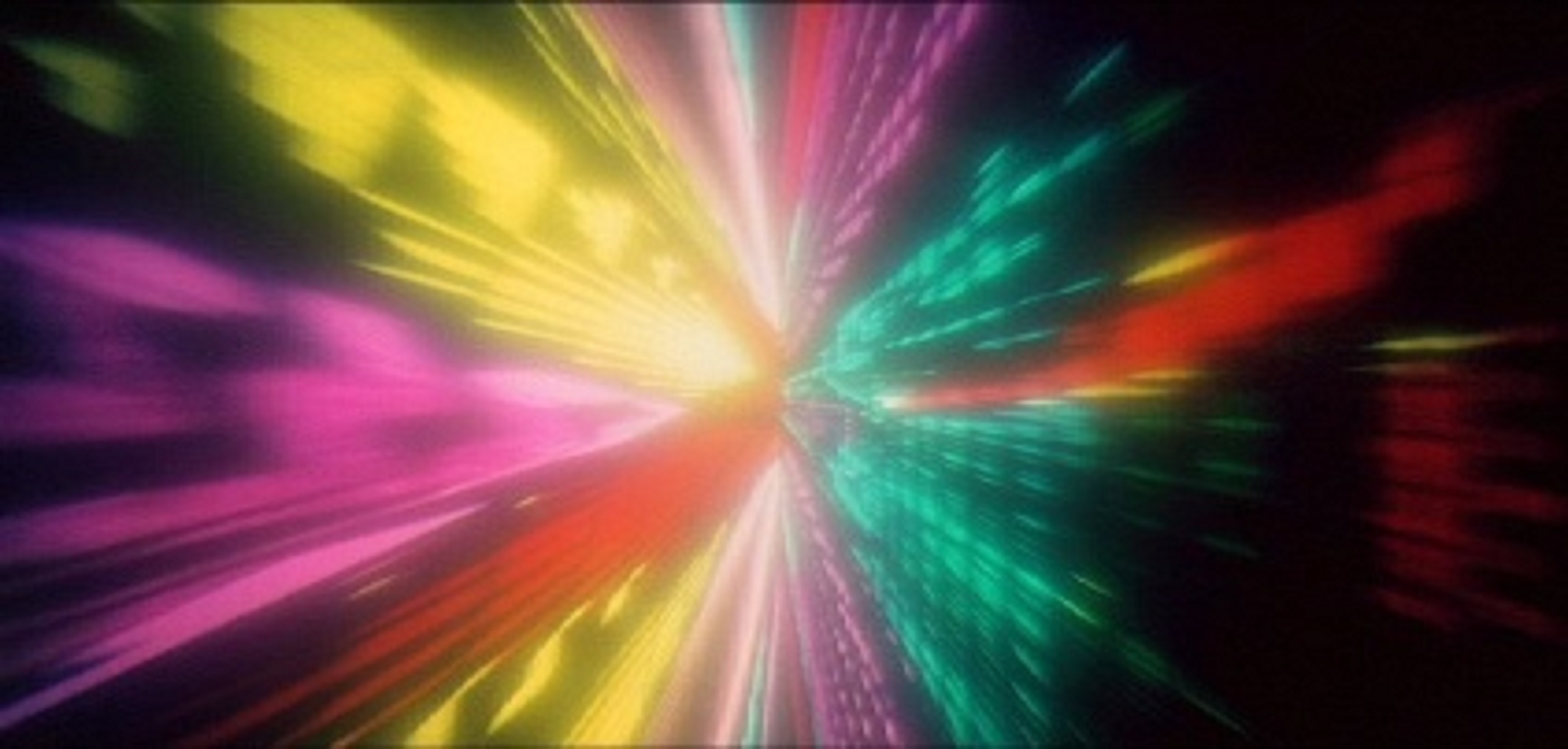

Dave gets himself out of the ship in order to investigate, but he is drawn into a swirling vortex of vibrant hues, the world around him transforms into a mesmerizing spectacle of otherworldly beauty. Celestial events unfold before his eyes, each one more peculiar and awe-inspiring than the last. Stars explode in bursts of iridescent colors, creating dazzling displays that paint the sky with hues never before seen by mortal eyes. Comets streak across the heavens, leaving trails of shimmering stardust in their wake, while planets collide in a celestial ballet, their collisions producing breathtaking showers of radiant light.

|

| This scene stretches for WAYYY too long, but it's impressive |

From a purely viewing perspective, it looks suspiciously like psychedelics, but we're going to ignore that.

Anyway, at the end of this verifiably confuddling scene we are brought to a pristine white bedroom - one of the things that I would say is pretty but wouldn't live in for the world.

The camerawork is astonishing.

He meets an older version of himself, donned in a spacesuit. Then the perspective flips, and the younger Dave has disappeared. Older Dave looks around confused, and sees an Even Older Dave having dinner. Even Older Dave is unconcerned by everything, until he casts his eyes upon the bed and noticed Deathbed Dave. The camera pans to Deathbed Dave, who is staring right ahead.

|

| The bedroom at the end of the universe |

A monolith.

At the foot of the bed.

Dave reaches for it, and once again Kubrick stops making sense to me. He is transformed into a foetus 'star-baby' surrounded by an inexplicable big white bubble and floats into orbit above earth.

Credits roll, and so do eyes around the classroom.

Everybody groggily exchanges glances, the Blue Danube piping away merrily as a black screen descends upon the whiteboard.

What just happened?

A little bit of digging, and there's some inkling of an explanation. According to Kubrick, Dave was meant to be taken in by god-like beings, beings made of pure energy and intelligence without any specific shape or form.

They placed him in what could be described as a human zoo, where his entire life unfolded from that moment onwards.

Time seemed to have no meaning for him, as events simply occurred as they did in the film.

They chose a room that was a highly inaccurate replica of French architecture (intentionally so) because it was believed that they had some understanding of what he might find aesthetically pleasing, although they weren't entirely certain.

This was a painfully accurate callback to my own comment on that scene. It's pretty, but I wouldn't live there.

It's similar to how we try to recreate natural environments for animals in zoos, even though we're not entirely sure if we're getting it right.

Once they were done with him, following a common theme in myths from various cultures around the world, he underwent a transformation into a "super being" and was sent back to Earth, completely changed and turned into some sort of superman.

What exactly happens when he returns is left to our imagination. This follows the pattern found in many mythologies, and that was the idea they were trying to convey.

But without all this context stick-taped by an internet connection, the movie itself seems very open to interpretation, and it is a testament to how the human mind can try and come up with explanations of its own. There are so many varied theories that have come out of critics and audiences alike to serve as an elucidation for what happened at the end.

But what happened at the moon landing, and why is Kubrick mixed up there?

Moon Landing Fake-outs

Simply put, the conspiracy theory is that the launch and splashdown would be real but the spacecraft itself would stay in Earth orbit and fake footage would be broadcast, directed by Kubrick, of course, as "live from the Moon." Can you believe it?

A French mockumentary called Opération Lune was made in 2002 to parody this conspiracy theory, involving fake interviews, far-fetched tales of the CIA assassinating Kubrick's assistants, couped with many glaring mistakes and puns all as part of the joke.

Naturally, this was taken seriously.

Later, another idea surfaced of Stanley Kubrick's brother, Raul, being involved in the American Communist Party (this was contemporary to the Red Scare), and NASA blackmailed him into directing the film.

Kubrick had no such brother.

Countless other pieces of 'evidence' have come up over the years, and have been debunked soon enough. Yet the idea remains.

How stubborn can one be?

Truly a testament to human willpower, is it not?

-BracketRocket

while i dont completely understand what happened in the movie (even with your stellar descriptions) as always a meticulously crafted article, stunning. also loved the barbie reference, a truly superior film. xx

ReplyDeleteThank you! It's a very difficult movie to describe in words, and there's a lot to unpack, even visually. I recommend you check it out, I think it can be streamed on Netflix now. It's a true milestone, especially for how it continues to influence so much of modern culture.

Delete